|

I was introduced to the wonderful world of neighborhood politics when I attended a monthly meeting of Manhattan's Community Board One.

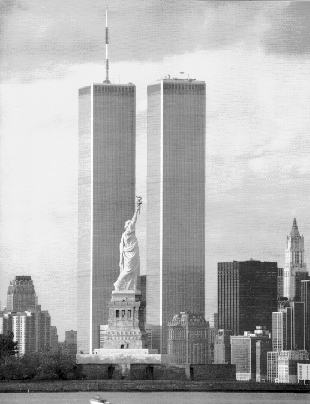

CB1 stretches from Battery Park all the way up to Canal Street, comprising the oldest and densest part of Manhattan. Over 26,000 people live in the district today, more than three times the population only twenty five years ago. Exiting from the subway, however, I passed very few people on the way to the meeting site at Stuyvesant High School. The commercial storefronts and old manufacturing warehouses filling the blocks showed little sign of human habitation. I crossed over the ten lanes of traffic all alone on an elevated bridge, and descended into what seemed to be another world. Surrounded by empty lots, chain link fences and construction debris, it was hard for me to see any signs of community at all.

It wasn't until I was inside the school's auditorium, however, that the 'community' suddenly appeared. There were quite a few button-down executives, as well as expectant mothers in jogging sweats, avant-garde types clad in black, even a pair of blue-haired old ladies, dressed in expensive designer outfits. In all, sixty to seventy people were milling about - some sitting in seats, others in small groups. With the board chairperson out on a vacation, Vice Chair Linda Roche and District Manager Paul Goldstein called the meeting to order from the huge stage. Their distance from the audience allowed a swirl of personal conversations to continue during the meeting.

As Roche and Goldstein called speaker after speaker to the microphone, the jovial tone of the meeting changed quickly. One board member enjoyed voicing his opinion on almost every proposal. Other members sat in the back of the auditorium, only saying yea or nay when it came time to vote. Many times votes were called to end long-winded speakers. In one instance, two board members who wanted a landmarks item repeated brought forth groans from the audience. The peer pressure forced them to abstain when they couldnt make up their minds.

The board's impatience was due to the long list of items to consider on the agenda that night. With several distinct neighborhoods making up CB1, the crowd was divided into separate factions, each with their own list of pet interests. The Battery Park City neighborhood committee was concerned about the impact of Route 9A reconstruction next to its apartments. The South Street Seaport Committee wanted to limit city vehicle parking in its neighborhood on weekends. The Tribeca committee was concerned about a delay in reconstruction of Pier 25, apparently caused by an infestation of teredoes - mollusks that feed on underwater pier pilings. A five minute discussion followed as to whether teredoes were mollusks or worms.

Out of all the issues discussed, though, only one galvanized the entire crowd. The Tribeca committee gave a progress report on a tree planting project along Greenwich Street. Doug Sterner, the committee chair, held up a six foot long, crudely drawn map of the street with big green dots representing trees. As he described what the committee had done since the last meeting, what seemed to be a simple little project of planting trees turned out to be an incredibly complex and negotiated process. Several city agencies were involved, along with the state economic development corporation, a Fortune 500 company, and the services of various consultants, surveyors, and lawyers. Even an underground sewer video filmed with a robot camera was a crucial element in getting the project done. After the presentation, the entire auditorium broke out into applause, acknowledging the committee's extraordinary effort just to bring a little nature to their neighborhood.

The meeting ended and I realized how important these trees were to the fledgling community. Living within the boundaries of Lower Manhattan forces a resident to go without many of the comforts taken for granted in other neighborhoods. Skyscrapers and street canyons do not jump out as places to raise kids or walk the dog. CB1 represents a residential community just now gaining an identity and a voice in city politics. Trees and parking spaces on the streets of Lower Manhattan may not seem like a big deal to most, but they represent a tangible sign of growth and community for those who live there. CB1 is unique because in many ways, it is a small town hidden within the shell of a metropolis. Its continued growth will make it difficult not to notice it in the future.

|